Wonderful wordless works of art

Some of our most engaging books for younger children are those which have very few words or no words at all. The illustrators of these wordless books are incredibly skilled in spinning a narrative through an unfolding sequence of pictures so exquisite, so imaginative, so carefully considered and sequenced that readers are immediately captivated and carried along. They convey action, tension and resolution with just a few strokes of the brush or pencil and images are nuanced to imply character traits and changing moods as the stories unfold.

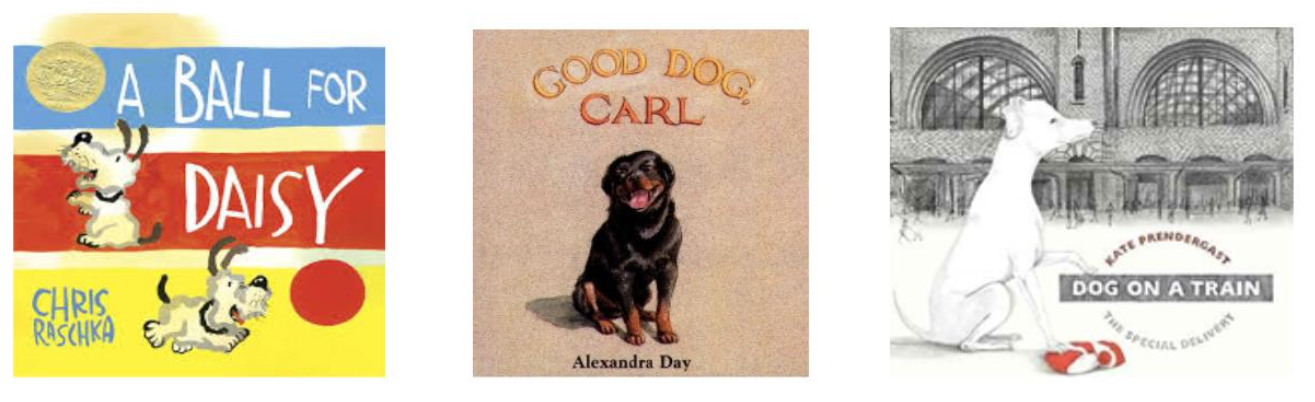

Canine wonders

One of the most charming wordless books is Chris Raschka’s Caldicot Medal winning A Ball for Daisy in which the eponymous terrier loses her favourite toy but finds a new friend. It is joyous, moving and utterly relatable for its early years’ audience.

Continuing the canine theme, adorable Carl, a most unlikely Rottweiler babysitter and his little human friend make mischief when they are alone in the house in Alexandra Day’s Good Dog, Carl. Readers are encouraged to collude with the central characters as their hilarious antics unfold. The brilliant evocation of would-be innocence on the final two pages is a fitting end to the story.

Dog on a Train by Kate Prendergast also explores the loyalty of a dog for his owner. Shading and colour are used to superb effect, capturing the dog’s mad dash through the London underground to reunite his owner with his woolly hat. The final page is sure to bring a lump to your throat.

Capturing Childhood

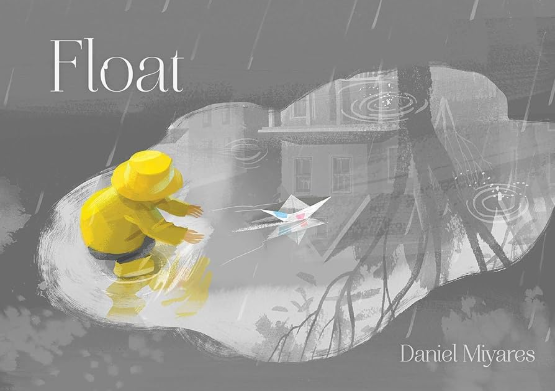

Some of the simplest wordless books probe the seminal experiences of early childhood. Float by Daniel Myares tells the powerful tale of the maiden voyage of a paper boat in an atmospheric study of grey clouds, raindrops, reflections, joy, disappointment and resilience.

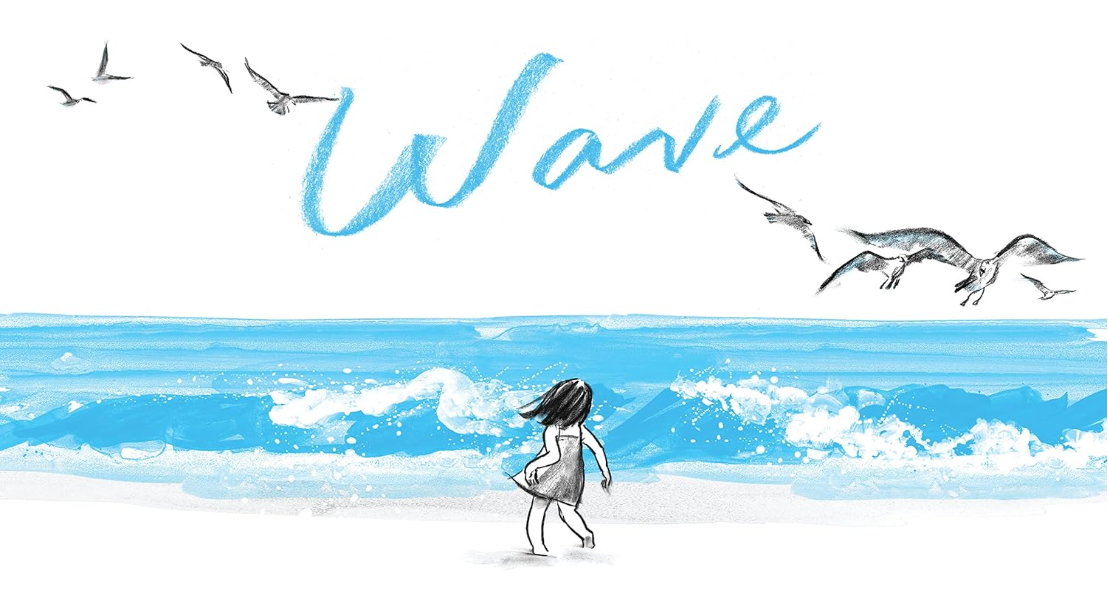

Suzy Lee’s Wave explores the enormity of a deserted beach and the drama of the incoming tide. With only a few pencil-strokes the author shows how the central character grows in confidence as she comes to understand this most special of environments.

Night time magic

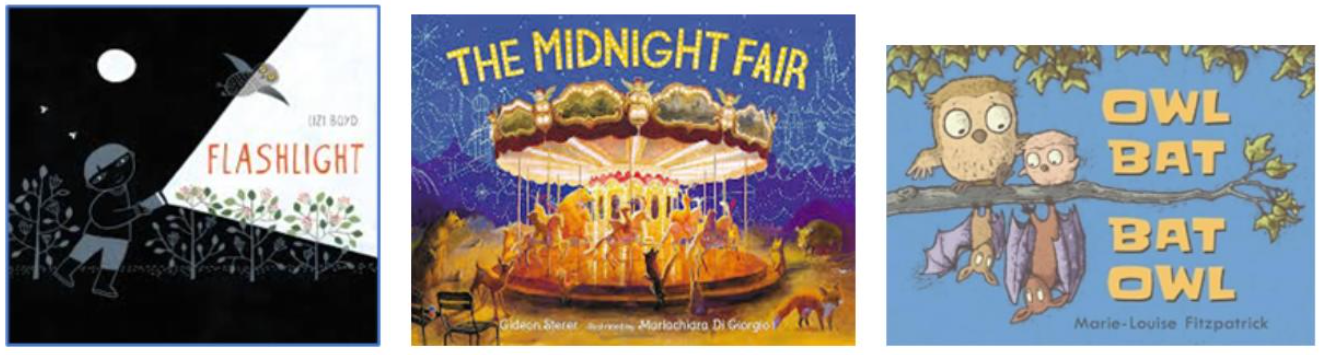

Lizi Boyd’s Flashlight is a delightful portrait of a forest at night. While it is ostensibly a point-and-name book, an emerging friendship between a boy and the woodland creatures is subtly threaded through the charming illustrations.

The special magic of darkness is also beautifully evoked in Gideon Sterer’s The Midnight Fair, when the forest animals snatch the opportunity for a turn on the rides before the fairground is packed away for another year.

Owl, bat, bat, owl by Marie-Louise Fitzpatrick is superficially a slapstick tale of nocturnal competition for a tree branch roost. Like many of these wordless tales it is, of course, much richer than that. There are important messages about sharing, about respect, and about integration.

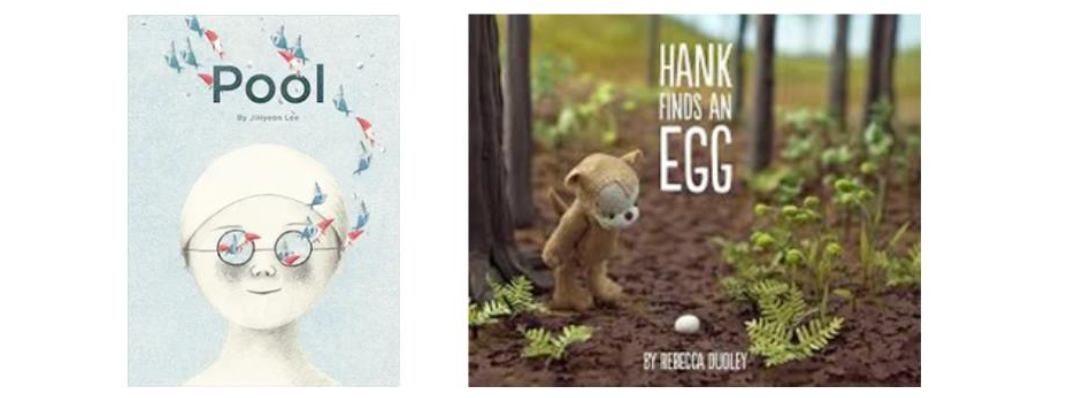

For sheer zaniness JiHyeon Lee’s Pool is very hard to beat. Here two lonely children escape the tedium of an overcrowded and unlovely public swimming pool by diving down…down…down into an astonishing oceanic world full of the strangest sea creatures.

Brilliantly illustrated and full of humour, each page is more intriguing than the last, but the message is loud and clear. Whatever wonders you may find in your adventures through this world, nothing is more beautiful than the friends you make along the way.

3D wonder

Amongst these riches it is almost impossible to pick a favourite, but Rebecca Dudley’s Hank Finds an Egg is surely one of the most appealing books in the wordless genre. The illustrations are three-dimensional scenes, photographed to tell the story of Hank’s mission to replace an egg in its nest. The attention to detail, subtle lighting, photographic skill and the heroics of the adorable central character come together to make a masterpiece. Only a reader with a heart of stone could be unmoved by the final ten pages.

Why wordless works

For educators, wordless books are rich in possibilities. They provide excellent scaffolds for narrative language and the details in the illustrations encourage ambitious vocabulary. There are opportunities to develop dialogue amongst the characters, perhaps even to consider sequels. However, the very first encounter should always be a slow and silent turning of the pages to properly appreciate these wonderful wordless works of art.

Article by

Catherine Worton

School Improvement Officer

Teaching, Learning, Curriculum and Leadership

catherine.worton@northtyneside.gov.uk